Copyrights 2022/23: Lexzau, Scharbau GmbH & Co. KG, Bremen (Germany). Concept and realization vibrio | Imprint | Privacy | Cookie Settings

Approximately 150 million TEUs (1 TEU = the size of a 20-foot container) are transported in global ocean shipping each year. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) has developed regulations based on the UN Recommendations, which are recognized in almost all countries. They form the basis for safe transportation anywhere in the world.

In everyday life, however, these regulations must also be implemented in practice. In this blog post, I’d like to share ten tips to help you stay on top of key container shipping issues in all situations at all times.

Since the introduction of standardized containers more than 60 years ago, many modifications have come onto the market, differing in many other details in parallel with the dimensions. In addition to the common 20-, 40- and 45-foot lengths in standard and high cube designs with various maximum permissible cargo weights, there are, for example, flatracks, open-tops, ventilated containers, refrigerated containers, bulk containers and tank containers. In principle, the selection is based on the needs of the shipper:

Based on these details, the shipper determines the type of container needed. For hazardous goods in tank containers, the permissible tank type incl. Additional requirements to be determined from column 13/14 of the Dangerous Goods List. If there is a need for advice on this, the freight forwarder will be happy to help.

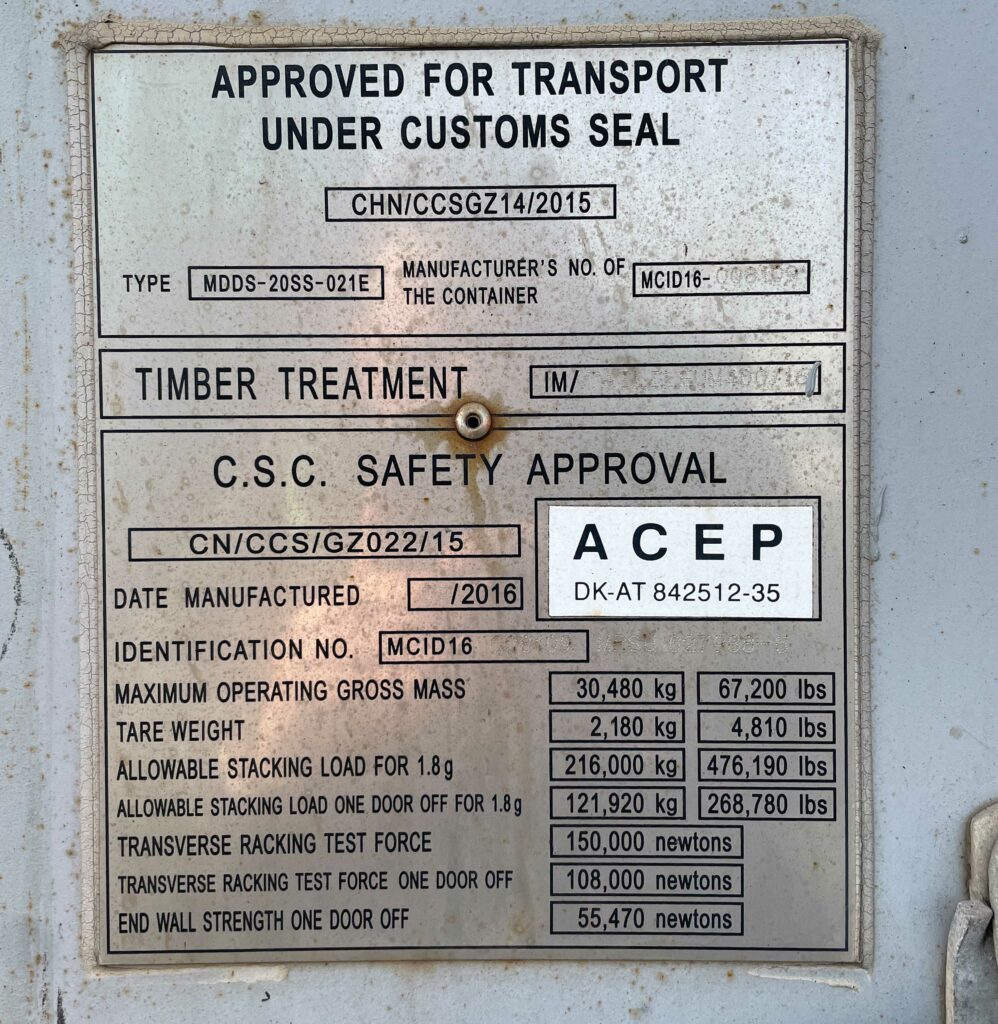

If the empty container is ready for loading, the container packer or filler must first check whether the container has the necessary approvals. In this context, abbreviations such as “CSC” and “ACEP” come up, which I would like to describe in more detail here.

Every container has to withstand extreme loads in everyday transport. An approval plate on the container door – the CSC Safety Approval – serves as proof of approval and regular monitoring. In addition to the date of manufacture, the gross maximum mass and the permissible stacking mass, the evidence of the regular inspections is also noted here (Next Examination / Re-inspection date). The first inspection is carried out after 5 years for brand new containers, then every 2.5 years.

This time-bound inspection program is hardly feasible in practice by the shipping companies. Many millions of containers would have to be inspected regularly. To save time and costs, the ACEP – short for Approved Continuous Examination Program – exists as an alternative to fixed dates. This is an officially approved inspection scheme that the container owner has defined for his container fleet. At larger transshipment points such as seaports or container depots, these containers are continuously monitored for damage. This means that a fixed date is no longer planned.

For the container packer this means: If a container has either a still valid date of the next fixed inspection or an ACEP entry on the approval plate, then the legal requirements for loading are in principle given. If neither is available, the further procedure should be coordinated before loading the container. In addition to the shipowner as the owner of the container, the container packer is also held responsible during official inspections. In the best case, only the ACEP sticker has come off the registration plate and can be replaced by the shipping company at the seaport.

Even if a container meets the legal approvals, the container packer must perform additional self-checks before loading. What are the important control points, and how are defects or damage to the container to be assessed? Are they structural hazards or merely visual impairments?

For the container packer, this is not a blanket assessment, as there are different repair standards depending on the shipping company. These also form the basis for the previously described ACEP procedure, which shipowners have defined and submitted to their competent authority. Accordingly, a container of the selected shipping company is serviceable as long as the described tolerances of the repair standard are met. A good basis is the standard IICL 5 of the “Institute of International Container Lessors”.

Within a structured list of container components, it is defined when damage such as cracks, creases or deep dents actually need to be repaired. These tolerances have been set by experts to ensure that the containers can be used in everyday life. Of course, the real transport and handling situations and conditions are taken into account.

Slight visual defects such as superficial rust or minor dents in the container walls that do not exceed the ISO dimensions of the containers (“Out of ISO”) can usually be tolerated. However, care must be taken when assessing the container floor: This usually consists of wooden panels that are bolted to the floor cross members and longitudinal members. If the bolts are no longer tight, the floor can bend when loaded by a forklift, or the protruding bolt heads can, for example, pierce barrels standing directly on the floor. So check carefully whether the floor appears uniform and load-bearing. If you want to use the lashing eyes on the floor and roof racks for your load securing, check them for durability and completeness.

Not tolerated are recognizably fresh contaminants and undefinable substances inside freight containers or on the outside of tank containers. This could be residue from spilled cargo during the last transport. If you have any doubts, contact your carrier. Moisture or condensation can also become problematic. Depending on the climatic conditions, moisture from warm air condenses overnight on the cool container walls and on the container ceiling. The drops then rain down onto the cargo and can soak cardboard boxes, for example. Unfortunately, this condensation, which can also occur during the sea voyage, can never be completely ruled out in the standard container.

In the course of the pre-carriage of dangerous goods to the seaport, several agencies are involved as a matter of principle:

In this transport chain, problems can arise especially at the interfaces. For example, a regular point of contention concerns the condition of the empty container. Who is responsible for the quality of the equipment, and who is liable for additional costs if a container is rejected by the container packer at the loading point and a replacement has to be provided?

Each party has its own argumentation here. While shipper and container packer usually refuse to pay the costs for good reasons, forwarder, carrier as well as container depot/shipowner discuss endlessly about cost allocation. Even if the empty container belongs to or is operated by the shipowner and the container depot is paid for by the shipowner, both refuse to share the costs of the misalignment. One argument in favor of this is that the truck driver could have rejected the empty container at the time of acceptance at the depot, so that there would not have been a wrong turn. Unfortunately, the argumentation is very one-sided. Picking up an empty container often takes place on the eve of presentation or early in the morning. Accordingly, the assessment of damage is to be carried out by the driver under time pressure in sometimes unfavorable light and weather conditions with legal certainty, which is not feasible in practice and would shift the responsibility unilaterally onto the driver.

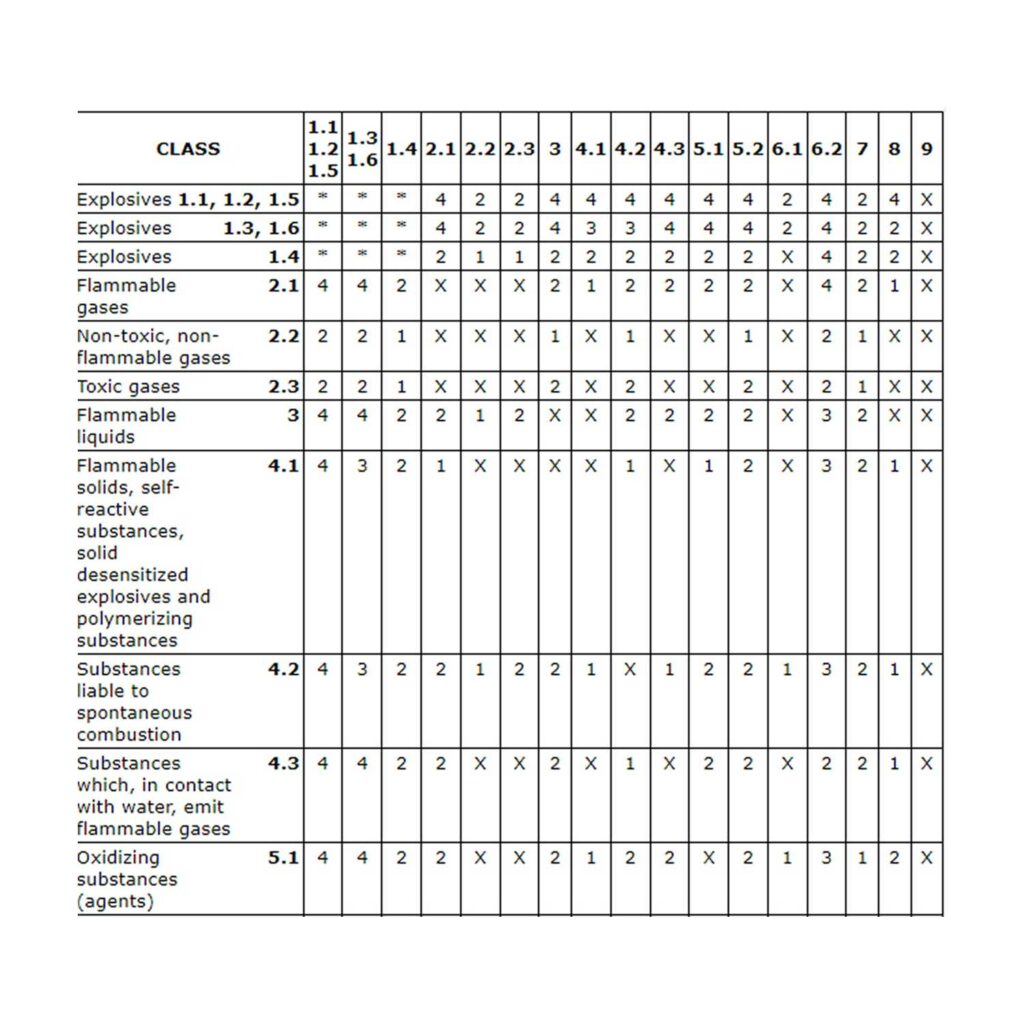

When combining dangerous goods for container loading, the segregation regulations of the IMDG Code must be strictly observed. If two or more different dangerous goods are to be loaded into one container, the separation table according to IMDG 7.2.4 is applied as the first step. This table contains the dangerous goods classes and the categorization with the indication “X” as well as the numbers 1 to 4. An important detail: If a dangerous substance possesses an additional subsidiary hazard (single subsidiary hazard label), then this must be taken into account in the separation regulations like a main class.

Check every detail of the dangerous goods (class and additional label) against each other. Each result must yield an “X” for this general feasibility check. Any numerical value means that loading together is not possible. Values 1 to 4 refer to distances and separations of dangerous goods from each other, which either cannot be observed in everyday transport or would require the acceptance of a competent authority and the shipping company.

Cross-checking the class 3 against class 4.1 gives us the clue X.

Cross-checking a class 3 substance with additional hazard 8 against class 4.1 gives indication 1.

How do we handle this information? As described before, the numerical values 1 to 4 lead to the prohibition of loading together. The “X” means “in principle it works”. But it must be additionally checked whether the individual goods have other, individual segregation requirements.

Because: In order not to make things too easy for the container planner, there are additional details to consider beyond the general table. These further segregation notes are called “Segregation Codes (SG)” and can be found in the IMDG Code in the Dangerous Goods List in column 16b. Attention: These notes go much further than the table in 7.2.4 and must be considered.

UN 1263 PAINT, class 3

UN 2556 NITROCELLULOSE WITH WATER, class 4.1

While the general table still returns an “X” here, UN 2555 contains the note “SG7, SG30” in column 16b, which means in plain text: “Stow away from class 3” and “Stow away from SGG7 – heavy metals and their salts”. Due to the note “Stow away from class 3” it is not allowed to load the dangerous goods from example 2 together.

The IMDG Code has even more special features in store here, which would go beyond the scope of this article. We will be happy to advise you further here.

Anyone loading a container must ensure in advance that the packages comply with the IMDG Code in all respects:

An important point in container loading is cargo securing. Unlike cargo securing on vehicles, a wide range of ship movement directions and inclination angles must be expected in maritime transport. In addition, sea voyages take much longer than road transport, and there are no possibilities to renew or improve cargo securing during transport. To prevent the load from moving, it must be secured starting from the most unfavorable combination of horizontal and vertical acceleration forces in the longitudinal and transverse directions. To achieve this, care must be taken to ensure tight fit during loading, and clearances between cargo items must be filled. Because: The load can slip due to the acceleration forces and thus be damaged. Depending on the nature and weight of the cargo, the load can be secured by a wide variety of means, such as wooden beams, certified belt systems or special solutions such as “Tygard 2000”.

The IMDG Code gives further instructions in chapter “7.3.3 Packing of cargo transport units” which must be observed by the container packer. They refer to the

For more details, please refer to the “CTU Code” (IMO/ILO/UNECE Code of Practice for Packing of Cargo Transport Units (MSC.1/Circ.1497).

Actually, this question is quite simple to answer: What dangerous goods are loaded into a container must be recognizable from the outside. But here, too, it is necessary to take into account special features. Dangerous goods labels, which are still called labels on the packages, are now to be enlarged to 25×25 cm. These placards are to be attached to all four sides of the container. As an aside, the label for “marine pollutants” (Marine Pollutants) is misleadingly referred to in the rule as a “mark” rather than a label/placard.

UN numbers on the container: If only one dangerous good with a UN number is loaded in the container and the gross weight is over 4,000 kg, the UN number must be shown in addition to the placard. The IMDG Code provides two options for this. The UN number may be shown in the placard within a white box or on a separate orange panel.

Labeling of tanks: For tank containers, the “Proper Shipping Name” must be affixed to the two long sides in 65mm high lettering. Attention: Font heights are remeasured sporadically by the authorities.

As a general rule, the material of the placards/marks/lettering as well as the attachment of these marking elements to the container must be able to survive three months in seawater. Think of past shipping accidents involving lost containers. Good to know what was packed in there in case the container washes ashore and gets opened by beach goers.

Basically, two documents are required for dangerous goods in freight containers:

A Dangerous Goods Declaration from the shipper – this accurately describes and documents the dangerous goods and packaging. The sender is responsible for the correctness and confirms this with a signature or the mention of the name of the responsible person (natural person). This document is intended for the forwarder, who needs it for further processing of the order and also forwards it to the shipowner.

A container packing certificate is issued by the container packer and is also signed. Hereby the responsible person confirms to have followed all details from IMDG 5.4.2.

Caution: If, for example, the load securing or container labeling is objected to during an official inspection, the authority will contact the issuer of the container packing certificate. A container packing certificate is issued by the container packer and is also signed. Hereby the responsible person confirms to have followed all details from IMDG 5.4.2.

Caution: If, for example, the load securing or container labeling is objected to during an official inspection, the authority will contact the issuer of the container packing certificate.

Both documents can also be combined, which is standard practice.

The dangerous goods law holds many more useful but also strange specialties. For example, there are special regulations for reefer containers with flammable cargo, regulations for the mixed loading of dangerous goods with foodstuffs, segregation groups, special temperature specifications for organic peroxides, exemptions for batteries, special additional certificates that must be supplied, shipping companies’ prohibition lists, and much more.

We will be happy to advise you further here. Just send us an e-mail.

The Leschaco Group is a global logistics service provider that combines Hanseatic tradition with cosmopolitanism and a spirit of innovation. “Experienced. Dedicated. Customized.” This is a fitting summary of the company’s philosophy: On the basis of decade-long experience teams of specialists set up customized solutions

› Sea Freight

› Air Freight

› Tank Container

› Contract Logistics

› Supply Chain Solutions

› Intermodal Transports

› Industrial Solutions

› Services

Lexzau, Scharbau GmbH & Co. KG

Kap-Horn-Straße 18

28237 Bremen

Deutschland

phone (49) 421.6101 0

fax (49) 421.6101 489

info@leschaco.com

Copyrights 2022/23: Lexzau, Scharbau GmbH & Co. KG, Bremen (Germany). Concept and realization vibrio | Imprint | Privacy | Cookie Settings